Thessaloniki gets ready for its metro launch in November

The underground rapid transit lines have been under construction for almost two decades due to various project delays

TheMayor.EU logo

TheMayor.EU logo

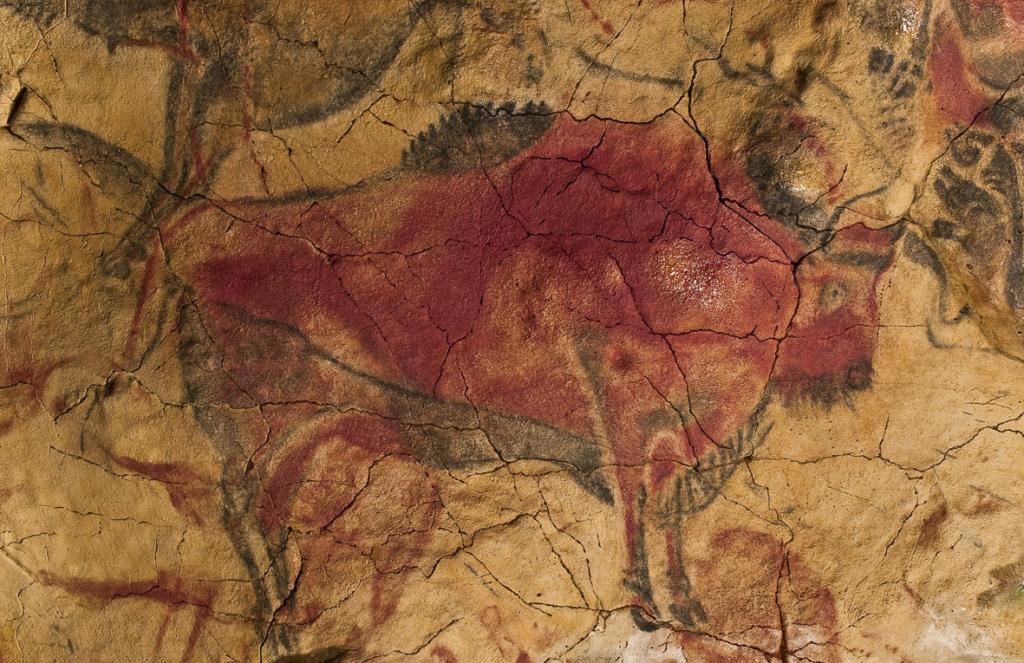

Bison painting from the ceiling of the cave of Altamira, Source: Museo de Altamira y D. Rodríguez, Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

In Cantabria, mountains bathe in the ocean and caves hide treasure troves of organic gems and prehistoric art

Cantabria, an autonomous region along the northern coast of Spain, is one of the few hidden jams in this overvisited country which ranked as the world’s second most preferred tourist destination before the pandemic (with 83 million guests in 2019, according to Luxury Travel Magazine). Although Santander, the region’s capital, is just an hour’s flight from Madrid, the majority of tourists coming to Cantabria are Spaniards mostly from the sun-parched areas, attracted by its milder climate, varied landscape of high mountains and sea, historical towns and excellent cuisine. The proximity of the warm Gulf Stream explains why temperatures there hover around 13°C in winter and rarely exceed 20°C in summer.

But Cantabria’s greatest treasure is hidden underground – literally. The region is home to 6500 limestone caves boasting the richest collection of rock paintings in Europe. The latter is proof that these stone hollows were not just a refuge to our Paleolithic ancestors, but also a temple and creative workshop.

Two hundred and fifty of these paintings, created some 28,000 to 13,000 years ago, can be found in the Cueva de El Castillo, a mountainous cave in the Puente Viesgo region. Holding our breath, we grope our way down to a dimly lit hall that resembles a cathedral – with a vault, a colonnade of stalactones, an apse, an altar and a niche with a Holy Virgin-like figure sculpted by nature. In the semi-darkness, our guide’s flashlight reveals figures of horses, deer, bison and fish painted on the walls with charcoal and red paint. These bison are said to have inspired none other than Picasso himself.

The realistic paintings alternate with abstract images – a row of big red dots that may represent a primitive calendar; parallel paint strokes ("that’s where they cleaned their brushes," the guide quips) and stylised images of sexual organs that were obviously used in fertility rites.

Cueva de El Castillo proves to be but a dress rehearsal for the spectacular show we’re treated to the next day in the Altamira cave near Santillana del Mar. More precisely, in the life-like replica of the original cave which has been painstakingly reproduced with the help of computers from millions of photos and video films.

The new, tourist-friendly Altamira cave reconstructs the way of life of prehistoric people through slide shows, videos and cleverly arranged vessels and tools. We soon realise why the Altamira is dubbed the “Sistine Chapel of Palaeolithic Art” – the ceiling is decorated with more than 30 multi-coloured figures of bison and other herbivorous animals painted with amazing skill 14,000 years ago. In the adjacent museum collection we make a jaw-dropping discovery: people in the Late Paleolithic age didn’t suffer from bad teeth, seriously!

At the entrance of El Soplao, we’re met by a statue of a miner, rusty wagons and a curious, egg-inspired sculpture by Bulgarian artist Dora Stefanova called “Muro de Mina” (“Mine Wall”). These exhibits reveal that the cave once housed a mine devoted to the extraction of minerals rich in zinc and lead. The mine was closed in 1979, and the Regional Minister of Culture, Tourism and Sport for Cantabria, Francisco Javier López Marcano, who himself is a miner’s son, had to work hard to persuade his colleagues that there was still money to be made from it, but this time as a tourist attraction.

We soon see for ourselves how farsighted he was. A railway takes us 300 m inside the cave, from where we continue on foot through an old tunnel. We hear the miners talking, the blows of their hammers, the rattle of the wagons. And we find ourselves in something unimaginable, to which the phrase “a never-ending white fairytale” won’t do enough justice.

Unlike the homes of the primitive hunter-painters, El Soplao’s interior is not the work of human hands, but of water rich in calcium carbonate. Thousands of years of dripping water, which seeped through the cracks, dissolved the limestone and transformed it into crystal, have embroidered the walls of the cave with fantastic ice corals.

There’s no other cave in the world where the eccentric formations known as helictites are so pure, so white and so many. But there is danger lurking in the wings. Vast deposits of amber have recently been discovered in El Soplao and the local authorities are wondering how to go about extracting the lucrative gem material without damaging the surrounding miracle of nature.

The underground rapid transit lines have been under construction for almost two decades due to various project delays

Now you can get your wine in Talence by paying directly in Bitcoin

That’s because the state has to spend money on updating the railway infrastructure rather than subsidizing the cost of the popular pass

Rethinking renewable energy sources for the urban landscape

The examples, compiled by Beyond Fossil Fuels, can inform and inspire communities and entrepreneurs that still feel trepidation at the prospect of energy transition

Now you can get your wine in Talence by paying directly in Bitcoin

The 10th European Conference on Sustainable Cities and Towns (ESCT) sets the stage for stronger cooperation between the EU, national and local level to fast track Europe's transition to climate neutrality.

At least, that’s the promise made by the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo

The underground rapid transit lines have been under construction for almost two decades due to various project delays

At least, that’s the promise made by the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo

Hostal de Pinós is located in the geographical centre of the autonomous region

Despite its church-y name, the district has long been known as the hangout spot for the artsy crowds

Urban dwellers across the EU are having a say in making their surroundings friendlier to people and the environment.

Forests in the EU can help green the European construction industry and bolster a continent-wide push for architectural improvements.

Apply by 10 November and do your part for the transformation of European public spaces

An interview with the Mayor of a Polish city that seeks to reinvent itself

An interview with the newly elected ICLEI President and Mayor of Malmö

A conversation with the Mayor of Lisbon about the spirit and dimensions of innovation present in the Portuguese capital