Thessaloniki gets ready for its metro launch in November

The underground rapid transit lines have been under construction for almost two decades due to various project delays

TheMayor.EU logo

TheMayor.EU logo Who can afford to buy a home in Bulgaria’s capital?

Affordable housing has been a persistent issue across the European Union for the past decade and a lot of capitals have become famous for their absurdly high rental and purchase prices. Meanwhile, Sofia often flies under the radar in that respect and the conversation on the affordability of housing is almost non-existent, both on the local and international levels.

So, what’s the deal? Has the Bulgarian capital managed to avoid the problem altogether? This is what I will try to find out in the first part of a series on affordable housing in Sofia.

Emil Hristov, an urbanist working for Sofiaplan and developing the city’s Urban Masterplan, explains that housing is one of the main resources that a city has. Yet, it is also a commodity subject to free-market principles, and a human right, at least, according to the European Union’s Charter on Fundamental Rights.

The housing sector in Bulgaria’s capital is driven primarily by realtors, developers and investors. Like many other countries in the region, local authorities have taken a laissez-faire approach to housing policy, partially motivated by the high rates of homeownership - an enduring legacy from the country’s Communist era.

However, it has been 30 years since the fall of said regime and the passage of time has deteriorated the buildings, together with people’s living conditions. According to a 2017 World Bank’s report, titled ‘Bulgaria. Housing Sector Assessment’ the housing stock in Sofia is in a bad condition, due to years of owner maintenance neglect. Likewise, there are a lot of vacant housing units and overcrowding rates are some of the highest in the European Union.

The affordability of housing is measured by comparing a household’s income to housing expenses. According to Eurostat, housing expenses include mortgage payments, housing loans, interest payments, rent, as well as utility costs, maintenance costs and insurance costs.

There are many ways to calculate affordability, but the most commonly applied rule of thumb is that housing expenses should be lower than 30 to 40% of a household’s income (30% of gross income; 40% of net income). If the household is paying more than a third of their income on housing, they are considered overburdened and have to start compromising with their essential expenses like food.

Ashna Mathema is a housing expert and the Founder of Total Housing Inc. She is also the main author of the publicly available 2017 World Bank report “Bulgaria: Housing Sector Assessment”. (Her views expressed here do not reflect the views of the World Bank.)She explains that, generally, housing is considered affordable if a household spends 30% or less.

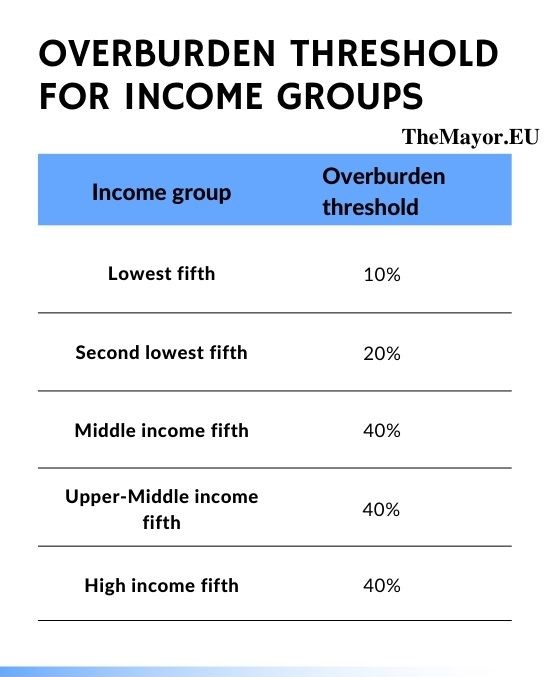

The World Bank’s report goes a step further, by providing an even lower overburden threshold for low-income households. This is because of the relatively high cost of food and utilities in Bulgaria, meaning that a household has a larger share of their money going towards non-housing expenses. The report divides the population into five even groups based on income and puts the overburden threshold at 10% for the poorest fifth of the population.

Overburden income groups,

Source: Bulgaria. Housing Sector Assessment, 2017

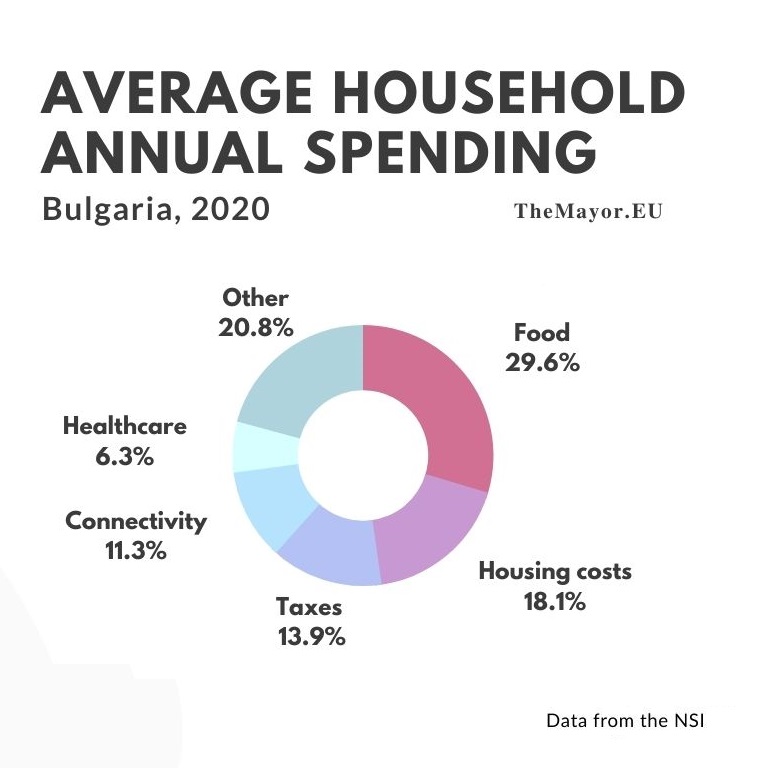

According to data by Bulgaria’s National Statistics Institute (NSI), the average household’s yearly costs for 2020 sat at 6,852 euros, while the average spending on food ate up 29.6% of that or around 2,028 euros. These figures are important because food has a relative floor and relative celling.

The average income per household, split into sectors,

The average income per household, split into sectors,

Source: Graph via Canva

At the same time, the NSI data suggests that the average household in Bulgaria does not experience housing costs above the overburdened threshold. This figure, though, can be misleading, as the country has a homeownership rate of around 84%. Most households are not paying for a mortgage.

However, this also means that the majority of housing costs are taken up by utility bills and they also have a relative floor and ceiling like food. Considering the overburden threshold for low-income households, the lowest two-fifths of the population have little to spend on maintenance, additional housing costs or moving to a better house. This issue is compounded by the relatively high overcrowding rates, recorded in the World Bank’s report.

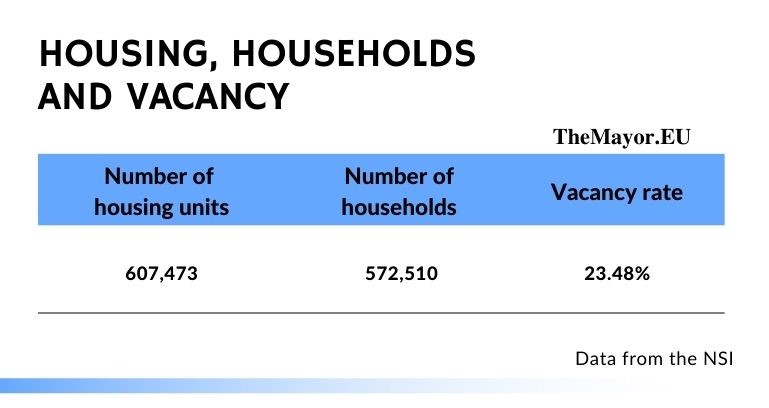

Another major issue is the number of vacant homes in Sofia – 23% according to the last census in 2011. This, however, does not necessarily mean an oversupply in the market as a lot of the homes are simply kept vacant. These include some that are held by investors for speculative purposes. According to Colliers, a real estate company in Sofia, a quarter of all purchases in 2021 were investment homes.

The number of households, housing units and vacancy rate,

The number of households, housing units and vacancy rate,

Source: Graph by Canva, data- 2011 Census

Some experts claim that a lot of people who own multiple homes prefer not to put them on the rental market as Bulgaria’s legislative framework is quite weak when it comes to protecting both renters and landlords.

The average number of people per household in Sofia is 2.2, while the total number of households is 572,510. The difference between the total number of homes and the number of households would suggest a surplus of 34,963 homes. However, factoring in the vacancy rate, or a total of 142,635 units, reveals a shortage. Simply put, those 572,510 households occupy 464,838 homes, showing a deficit of 107,672 housing units. According to this data set, 1.2 households are sharing every inhabited housing unit.

Furthermore, the age a young person in Bulgaria leaves their home has gone up by two years between 2004-2020 and now it sits at 29.9. This suggests that more and more young people might be having trouble accessing the housing market in terms of rent and purchasing.

The data from the World Bank report on housing seems to confirm this point as it found an extreme overcrowding rate in Bulgarian cities - 48%. For children and teenagers, it is 79.8%, while in the 16 to 29 age group it sits at 58.8%. Renters, on the other hand, are at a whopping 82%.

In fact, according to the same report, 15.5% of Bulgarian homeowner households constitute of 3 or more adults with dependent children, which is nearly three times the percentage for EU-27 countries. This suggests doubling or even tripling of households in a single home.

All this goes to show that those 1.2 households per housing unit are not spread evenly, with children and young people being particularly affected by the overcrowded conditions. Given the circumstances, this points to a conclusion that a lot of people cannot afford both to rent or buy.

There is a distinct lack of useful income data in Bulgaria. NSI appears to be a poor resource when it comes to gauging the dimensions and implications of the housing affordability problem. Emil Hristov makes this point too, as he stresses the need for further research on part of the government before it starts implementing portions of the Sofia Urban Masterplan.

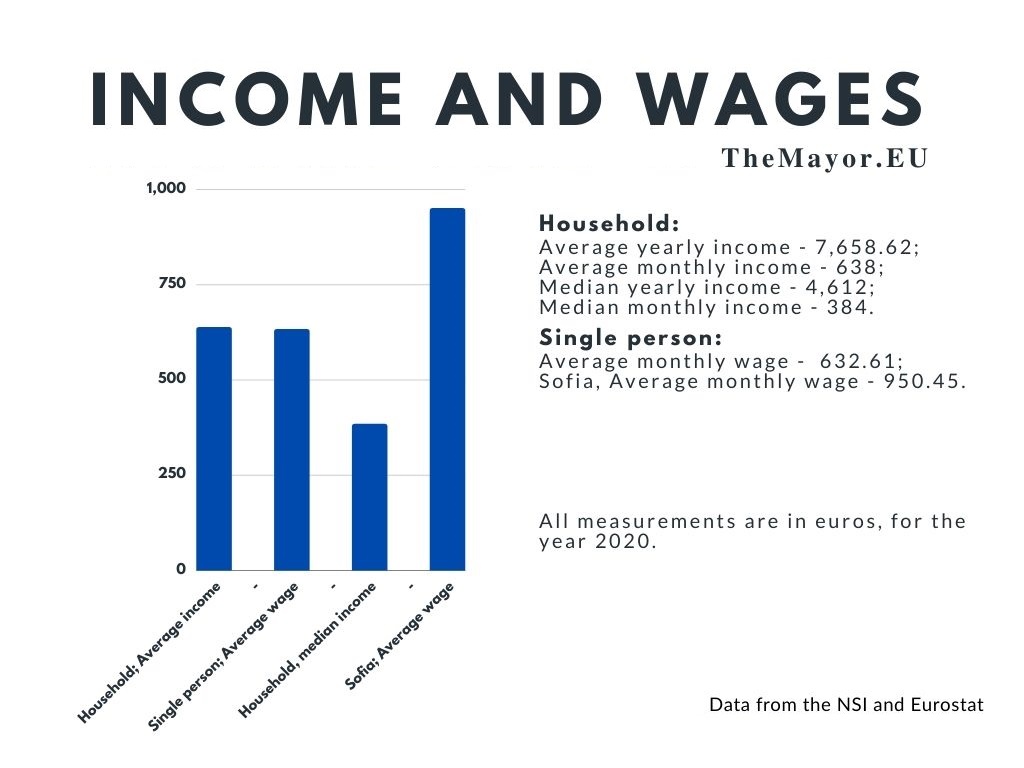

Wages and income per person and household in Bulgaria and Sofia,

Source: Graph by Canva

As a clarification, median income is the income amount that divides the population into two equal groups, half having income above that amount, half – an income below that amount.

A striking point in the data is the average household income to average wage per single person ratio. Two factors could be responsible for this: the significant grey economy in the country and the large number of households with dependent children or elderly, discussed above. It also suggests a high amount of households have a single breadwinner.

At the same time, the median household income is nearly 40% lower than the average. This means that half the households in Bulgaria earn 40% less than the average income household. This is because Bulgaria has the highest income inequality rate in the European Union. In Sofia, the median household income is likely to be significantly lower than the average.

There are two ways I will try to measure the availability or lack of affordable housing. One is to pinpoint the sort of average home and the costs of buying it with a mortgage. The other is to take the cheapest possible home and see who can afford it. The only caveat I have is that I will use only already constructed homes, regardless of whether they are new because I want to assume that a family wants to move in immediately.

Let us imagine an average apartment in Sofia. According to NSI data, the most common apartments have two to three bedrooms and are about 90 square metres in size.

According to Imoteka, a real-estate company in Sofia, the average asking price per square metre in the city is 1,384 euros in 2021. This imaginary apartment costs 124,560 euros and it is sought after a household of two people, who probably plan on having a child, (considering the 2.2 people per household number). In Imot.bg, Bulgaria’s biggest real-estate website, there are a lot of listings that fit the bill and most of them are found in older buildings.

According to the World Bank report, the loan to value ratio (LTV) for older homes varies between 70% and 75% of the total cost. For this calculation, let’s use a mortgage covering 75% of the price. That means that the down payment would be 31,140 euros and the mortgage should cover 93,420 euros. This makes the monthly payment on a 20-year mortgage with a 3% interest rate of about 519.85 euros. Of course, the exact amount is dependent on the bank and the negotiated terms, however, conditions do not differ dramatically from this estimation.

Now, let us take that 519.85 euros and make that our housing costs, as a conservative estimate. Note that utilities can eat up around 14% of a household’s income, however, it’s hard to untangle the NSI’s data and get a precise number. Considering that housing costs need to take up no more than 30% of a household’s income to be considered affordable, this one would need to earn 1,732 euros per month to purchase the average home. This is near twice the average wage for Sofia and around 2.5 times higher than the average national household income. Furthermore, to be able to afford the down payment, the buying household needs to save up around a year and a half of their full income.

Emil Hristov points out that finding a domestic partner can turn into an economic decision, especially if that spouse is employed. This could potentially double your opportunity to obtain a home.

Now let us look at the bottom of the market. At the time of writing, in Imot.bg, the cheapest property for sale was a 26,999 euro, 25 square metres one-bedroom apartment in need of repairs.

The down payment on this apartment should be about 6,749.75 euros while the monthly payment adds up to 113.63 euros for the next 20 years. Now, instead of the 30% rule, let’s take the overburden threshold of the second-lowest income group – 20%. This means that the household income needs to be about 568.15 euros – just over the poverty line (200 euros per person). Keep in mind that this estimation does not factor in the additional cost of gas and maintenance.

This household would barely be able to afford to move in and would likely not have the money for repairs. They would also need to save up a year’s salary to afford the down payment, and that is no easy task when living close to the poverty line.

This means that the second-lowest income group could afford this apartment in theory, but not in practice. It also means that the bottom 40% of income earners practically cannot afford any properties on the market and it looks like the unaffordability bracket extends upwards.

All the data points to a housing problem in Sofia. The high-income inequality, high vacancy rates and the doubling and tripling up of households, as well as the rise of investment apartments, shows a market that is getting more and more exclusionary, especially when it comes to affordable options for starter families, single-person households and single-parent households. Overcrowding, in particular, points to a lack of viable housing options and a highly constrained rental market.

Furthermore, the World Bank report states that as much as 50% of households in the country cannot afford or choose to save on housing costs by foregoing maintenance and repairs. This means that there is a hidden cost when purchasing a home – the cost for repairs. This drives unaffordability further and it makes a lot of buildings seem impermanent.

While the relatively high homeownership rate of 89% provides a buffer for low-income households, the level of real-estate investment purchases threatens to lock these households in an overcrowded state. If things stay the same for the near future, the only feasible advice to wannabe homeowners in Sofia seems to be: find a well-earning life partner or get paid twice the average wage.

This article has been updated.

Follow TheMayor.EU to read the second part of the story, where Emil Hristov and Ashna Mathema discuss what the cash-strapped Sofia Мunicipality can do to fix the problem.

The underground rapid transit lines have been under construction for almost two decades due to various project delays

Now you can get your wine in Talence by paying directly in Bitcoin

That’s because the state has to spend money on updating the railway infrastructure rather than subsidizing the cost of the popular pass

Rethinking renewable energy sources for the urban landscape

The examples, compiled by Beyond Fossil Fuels, can inform and inspire communities and entrepreneurs that still feel trepidation at the prospect of energy transition

Now you can get your wine in Talence by paying directly in Bitcoin

The 10th European Conference on Sustainable Cities and Towns (ESCT) sets the stage for stronger cooperation between the EU, national and local level to fast track Europe's transition to climate neutrality.

At least, that’s the promise made by the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo

The underground rapid transit lines have been under construction for almost two decades due to various project delays

At least, that’s the promise made by the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo

Hostal de Pinós is located in the geographical centre of the autonomous region

Despite its church-y name, the district has long been known as the hangout spot for the artsy crowds

Urban dwellers across the EU are having a say in making their surroundings friendlier to people and the environment.

Forests in the EU can help green the European construction industry and bolster a continent-wide push for architectural improvements.

Apply by 10 November and do your part for the transformation of European public spaces

An interview with the Mayor of a Polish city that seeks to reinvent itself

An interview with the newly elected ICLEI President and Mayor of Malmö

A conversation with the Mayor of Lisbon about the spirit and dimensions of innovation present in the Portuguese capital